Revision of a Work Should Constitute 75 Percent of the Writing Process

The faint of heart might not want to read this post.When I taught writing at the university level the students and I had a limited amount of time to cover a great deal of material. During the years that I taught writing, it was almost a universal that students (freshmen, sophomores) came to college ill prepared in English and composition. And I had to balance the needs of those students against the older returning students who had been out in the real world and saw that they would never advance very far if they didn't further their education. These students came with much higher expectations about a writing class than the eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds.

But both kinds of students had a difficult time accepting the notion that what you first write is not the finished product. I had a penchant for assigning controversial topics to be covered in their essays. I was amazed that they thought a paragraph on the pros and a paragraph on the cons were enough to fully state their positions and to be convincing. They were amazed when I made them redo the essays. If I had had more time, I would have had them revise the same essays throughout the semester.

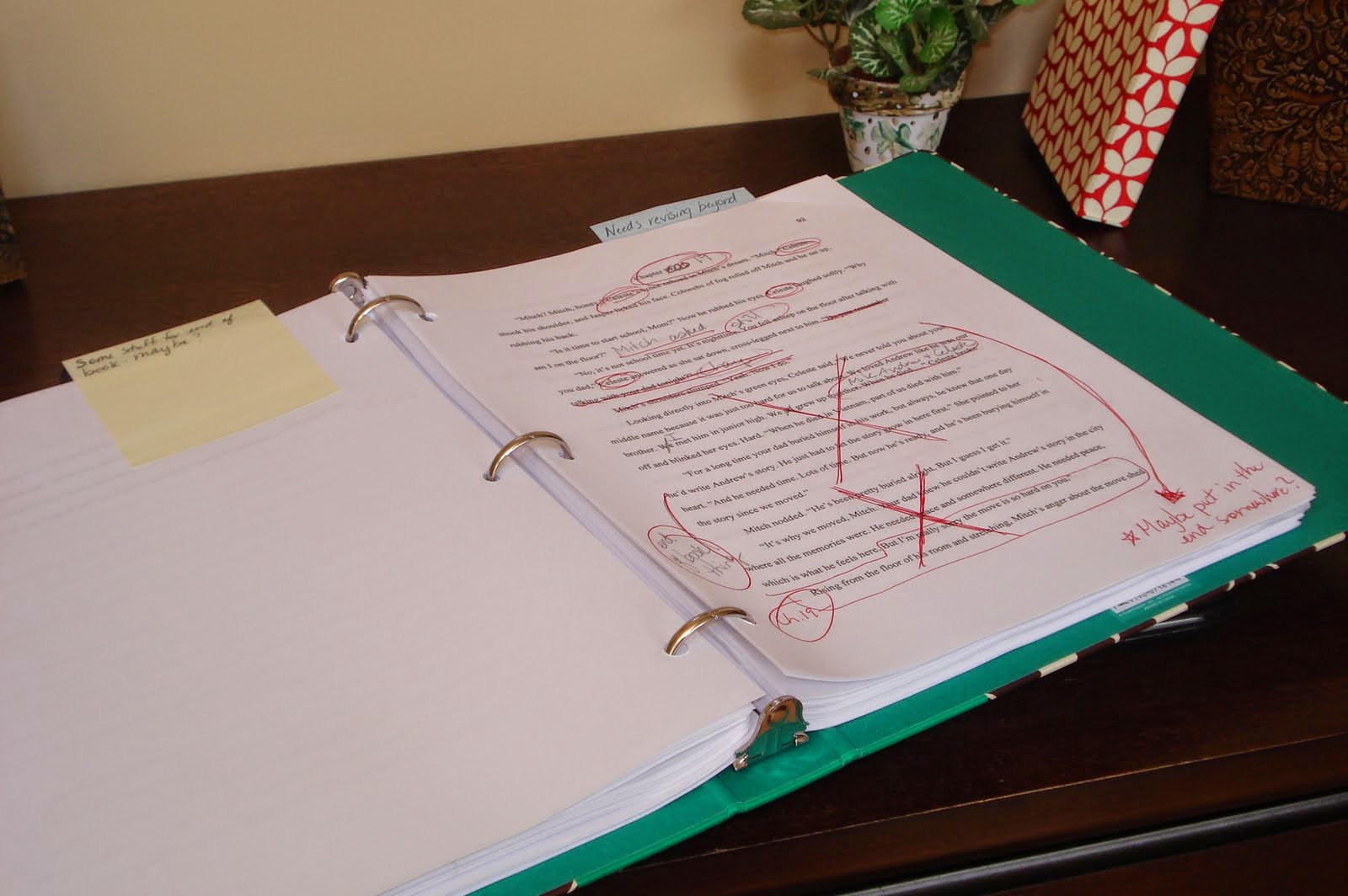

Yes, even seasoned writers can get absolutely sick of revising the same work, along about the fifth full revision. On the other hand, I love revision. To me, it's where the true magic of writing takes place. It's where the finished product reads as if writing it was effortless, where it appears that the words just flowed in a bubbling stream from start to finish.

But Joyce's work is almost impenetrable to casual readers, while Hemingway's work is cut to the bare bones. Yet both are considered great literature. One's style is challenging in vocabulary and syntax and is intimidating from the very first sentence, while the other's style is deceptively easy to understand and accessible to readers. They did not achieve their goals by writing a single draft. Their style and substance came through precisely because they revised and revised again and again.

James Joyce: Finnegans Wake

“riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.”

Ernest Hemingway: The Old Man and the Sea

He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish.

Between these two extremes of expression lie most writers. In a sense, one revises a novel to achieve a consistent voice, both for the way in which the story reads and the narrative voice.

Let's come up with an idea for a novel, right now; then let's write a complete first draft...

There. That took about 25 percent of our time.

Coming up with the idea for the novel probably took 10 percent, and writing the first draft took 15 percent. Now we're a quarter of the way through the entire writing process. See the previous post "Editing Comes in Stages" about halfway down, for a detailed list of things we should consider when we set out to revise a novel. In truth, this is only part of the process of revision.

Basically, when we revise a completed work we look at everything, both narrative and technical.

- Plot/structure

- Plot flow/subplots (story lines)

- Character and setting description

- Dialogue

- Narrative voice

- Narrative tense

- Syntax

- Grammar

- Punctuation

- Spelling

- Word choice

As an editor and one who evaluates other writers' books, I can tell what parts of the novel the writer has worked and reworked and which parts he/she has not addressed as fully. I have a tendency to revise the opening of my novels more than other parts, but eventually I make two or three major sweeps through the entire novel—and then it's off to an editor. I would never consider it finished until an independent set of eyes went over it. And then I revise it again, fine tuning it.

When I evaluate a novel for another writer, and let's say the novel contains graphic sex, I can usually tell just how important such scenes are to the writer over and above the parts between the sex scenes, not only by their frequency, but also by how descriptive they are in comparison, say, to the dinner the suitor has taken the date to prior to getting him or her into bed. In that case (seeing that the writer's focus was on the graphic sex), I will usually have to point out other parts of the story that need to be revised to balance out the detail and description of the graphic sex scenes.

But seriously, it is through revision of a thousand different considerations where a novel finally begins to take on its final shape. In my early days, I also sent half-baked "finished" novels to friends and family to read and comment on. Even the gentlest of readers had questions, lots of questions that I hadn't even considered, and through time, I incorporated such questions into my own revision strategy. My style is to pair down on the language, to use simple Anglo Saxon words and fewer French-based words that have made their way into English, which makes my style more like Ernest Hemingway and a lot less like James Joyce. But this does not come naturally, I have to work at it through revision.

Revision also takes on a life of its own when we consider historical novels. The author has to appear to write effortlessly about historical facts that imbue the narrative with authenticity. And that takes a great deal of research. The historical facts have to be incorporated into the story in such a way that they are not consciously historical but common and familiar to the characters, even though readers know that the author is a modern-day writer and did not live in the period about which he/she writes. The same can be said about science-fiction novels. The writer no doubt has to do a lot of research to get the science just right, or astute readers will choke on the bad science concepts. But then, almost every genre has its own knowledge base. Police procedural novels have to ring true, and I have read about writers who get themselves assigned to a police department, go out on calls, and observe the processes in a police station.

Because of these requirements to achieve verisimilitude, the adage to write what you know is very good advice. If you've never flown a jet, you have a lot of research to do before your main character is a believable jet pilot.

I have a feeling that this post topic is too important to attempt covering all the aspects of revision in one sitting. So...to be continued...

No comments:

Post a Comment