Six Distinct Ways to Develop Character

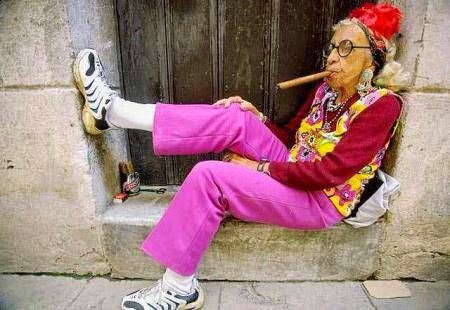

1. Head to toe physical description

2. Unique physical and other characteristics

3. How a character acts and reacts

4. What a character says about himself, about others, and about issues

5. What others say about a character and how that character responds

6. What a character thinks about

Other writers will no doubt come up with other ways to develop characters. In the nineteenth and earlier centuries, writers often used a character's name to indicate the kind of person a character was: Mr. Goodfellow, Snidely Whiplash, etc. But we also see modern-day examples: Miss Ballbricker (Porky's, the movie), Doug and Windy Whiner (SNL). Using names for characters that indicate a character's type is fun, but be careful not to overdo it. These days it often creates a comic mood.

Character physical description, along with unique physical characteristics

New writers often overlook a real physical description of their characters. My general rule of thumb is that as soon as a character is introduced in a story, readers should get a good first look at as much of the character as possible, followed by something unique in the character that distinguishes him or her from everyone else in the story. Of course there is the danger of intruding upon the story to stop and describe the character. But writers should find a way to sneak in the description at the earliest possible moment, without woodenly stopping the flow of the story.

I suggest a top-down description:

When Leo came in from the rain, his normally curly black hair was plastered to his head, and the ringlets dripped water onto his face, as if he were sweating. His brow was creased, and his coal black eyebrows were drawn together resembling the wingspan of a predatory bird in flight. His deep blue eyes with girlishly long eyelashes, were unfortunately hidden behind thick-lensed glasses. They rode on the tip of his nose, which he pushed to the bridge of his nose against the insistent moisture on his face. In calmer moments people noticed his full and rather pale lips, which were pressed into a thin line at his wet discomfort. He pulled the backpack off his right shoulder and set it on the floor beside the first table he had come to in the coffee shop, and then he struggled out of his wet sports jacket. Normally, it hung on his thin shoulders like he'd borrowed it from a big brother. And once he'd removed the jacket, he flung it on the back of a chair at the table. He'd worn what he thought was his best dressy blue shirt, and it too clung to his undeveloped chest like a second skin. His corduroy slacks rode a little high on his trim waist. He was six feet tall, and fully half of that was waist, long thighs, and chicken-leg calves that prevented him from wearing shorts, as "chicken legs" was the first thought that came to him when he looked in the mirror. He'd worn Hushpuppy shoes and they squished as he managed to finally take a seat, trying to relax, having no idea that his usually chronic red cheeks, which some people mistook for a healthy demeanor, was now splotchy and hot looking, as if he were running a fever.

The above is definitely not great literature, but we learn several things about the character, Leo, just from the physical description, how he carries himself, how he is flustered from having gotten soaked before he got to the coffee shop. We also manage to describe his clothing, as well as a distinguishing characteristic in his chronic red cheeks. Yes, he might have Rosacea. We know that if he were not wet from the rain, his outfit would indicate that he had made some attempt to dress up, wearing his best dressy blue shirt, a sports jacket, and was going for a casual, well-dressed appearance. In entirely young, twenty-first century story of teenagers, we might also see that his dress would be considered nerdy. The thick-lensed glasses are a good start. Have them be taped on one of the earpieces, and the effect will scream "nerd!"

A writer can also choose to do a bottom-up description, which can be effective, let's say if a character is lying on the pavement having been attacked by an assailant, and when he comes to and another character is standing over him, it would be natural to begin with the shoes and work his way up to the face of the person standing over him. There are also scenes in movies where the first thing we see of a character, let's say of a beautiful woman arriving at a red-carpet affair, is her shoes as she steps out of the limousine onto the sidewalk, followed by her shapely calves, her clingy red dress, that shows off her lithe figure, and so on as we follow her movements out of the car, up her body, until we get a full view of her.

But it is also natural in real life that once we get an overall view of a person, we concentrate on the face, the eyes, the mouth, and whatever distinguishing characteristic that makes that person unique. Sometimes it is a limp, a missing limb, an overly large nose, any one of a million features.

How a character acts and reacts

This way of developing character can be used over and over throughout the novel. Maybe the local football star slaps Leo on the back, just as he's about to take a sip of latte, and we can see Leo cringe (indicating timidity, fear, or even feckless annoyance against a greater, more powerful character). Now let's take a look at how the football star comes into the same coffee shop, also soaking wet. He would no doubt be laughing and jovial, having enjoyed the spectacle of himself, and we can almost see him shaking off the water like a German Shepard coming in out of the rain. In fact the local football star might really like Leo and is simply not aware of his intimidating presence or the sudden discomfort he causes in Leo, when he slaps him on the back. We see these opposite actions and reactions in many scenes in both novels and movies, and it gives readers a chance to see into the personality of both characters at once. I'm going for the obvious action and reaction in simple scenes to show how we get a feel for a character as the story unfolds. But there are all kinds of nuances of character body language that can illustrate personality.

What a character says about himself, about others, and about issues

(Here, we'll also show character direct and indirect thoughts during dialogue. This is part of the sixth way we reveal character traits and personality)

When we engage characters in dialogue, we have an opportunity to reveal further character traits. From my

Two Brothers Press website, I have extracted a dialogue scene between husband and wife that shows how what they say, what they think, and how they react to each other reveals all sorts of character development. I have used what would be mundane dialogue, "What's for dinner?" (which I caution against) as a vehicle to carry the character development of both husband and wife:

"What are we having for

dinner? John asked, almost shouting as soon as he stepped into the

house, slamming the door behind him. It had been a hard day and he

hoped his wife would hold up her end of their rotten marriage and feed

him a good meal.

"Pizza," Betty shouted back. Whether John realized it or not, she

worked just as hard as he did, and she wasn't about to slave over a hot

stove, only to see him wolf down his food, fart, and move off to the

living room to vegetate in front of the TV.

"What kind of pizza? John asked, irritated that Betty had once again ordered in their food. It better not be pepperoni, he thought. She knows it irritates my colon.

"Pepperoni," Betty said, lowering her voice, almost growling, daring

John to complain. She wasn't about to work her ass off for him and

never would again, since she'd found out he'd been boffing the

secretary—and a good bout of methane gas and bloating would serve him

right. Does rat poison look like parmesan? she wondered.

We can learn a great deal about the personalities and kind of characters these are by their actions, although nothing in what they say reveals personality traits. We see that the wife Betty has a passive-agressive personality by serving pepperoni pizza to her husband. While she barely does her "wifely" duty as John thinks she ought to, she refuses to really do his bidding, and she is punishing him at the same time, knowing that he will suffer from intestinal distress. The husband of course is a selfish person; he has his "fun" on the side with his secretary and yet still expects his wife to be there for him when he gets home. What I also tried to show is

if writers must discuss mundane topics (and what's for dinner is surely among the mundane), it can be done in such a way that we get a great deal going on under the surface, not only by what is not said, but what each character thinks, in both direct thoughts (those that are italicized) and narrated thoughts (written in third person by the story narrator). Further the dialogue description (Betty lowers her voice and almost growls her answer), shows that she is angry. John's actions of slamming the door and almost shouting his question also reveals his state of mind.

What others say about a character and how that character responds

Now, let's continue with another way to develop characters with Leo, Dave the football star, and a bully named Chad to reveal character traits, by what characters say about another character and how a character responds. To avoid cluttering up the example, I'm going to avoid detailed description of setting as the dialogue unfolds. It's still in the coffee shop, and to Leo's dismay Dave the football star has sat down at his table, and he is joined by Chad, the most popular non-athlete in the school.

"So, four eyes, did you get my research paper done?" Chad asked. He leaned forward and grinned widely showing his perfect teeth, and it hit Leo that he probably practiced his million-dollar smile in the mirror.

"Um-yeah," Leo said glancing at Dave and then at Chad. He pulled the still dripping back pack from the floor and rustled through a compartment until he pulled out a rather damp-feeling sheaf of papers. He was appalled at how the ink-jet printer ink had feathered into the paper, just enough to make the type look out of focus. "Um...it's damp. sorry."

Chad snatched the research paper from Leo's grasp and thumbed through it, as both Dave and Leo watched. Chad looked up. "Redo it, you little chickenshit. I can't turn this in."

"Uh—okay. I'll get it to—"

"You're not doing any such thing, Leo," Dave said, flicking the edge of the paper. "You spent enough time." He turned his focus on Chad. "Make do with it, you moron," Dave said directly into Chad's fading million-dollar smile.

In this really bad example, we see that Chad enjoys intimidating others, and of course he comes up with demeaning ways to inflict embarrassment on Leo. We see that Leo is painfully compliant, and this is a personality trait, at least in his overt reaction to what Chad says. We also see that in his mind, Leo sees through Chad's outward personality, knowing that like everyone else, he must practice the kind of mask he wears in public, flashing an obviously practiced smile.

And we see Dave's personality. He's impatient with badly behaving people like Chad, and perhaps his utter lack of self-consciousness allows him to be direct, telling Chad to accept the paper, damp or not, and be satisfied.

We can imagine the three young men's conversation either ending abruptly as Chad takes the paper and leaves the table, or we can see that perhaps he puts up resistance to Dave's demand that he accept the paper. We think that Dave will probably win this round, and we also see that he's rather protective of Leo.

What a character thinks about

As we saw in the above example, we get a hint at what Leo thinks about, and it reveals a bit of insight into his personality, when he realizes that Chad must practice his looks in a mirror. But more important than the internal thoughts that might accompany dialogue, we can use "what a character thinks about" to reveal much deeper aspects of a character's personality. When we see a character by himself, engaged in thinking, the writer needs to realize that

there can be no lies. The character's inner thoughts must reflect how they really feel about things, how they really are, when they're by themselves. This is where evil and goodness are revealed in our main characters. I use the terms "evil" and "good" loosely, because it doesn't have to be murderous evil, just

not good. When we see Chad alone, his thoughts might reveal how he enjoys controlling little nerds like Leo to do his bidding, or we might even see that he reveals his own fears and self-concept issues. We might see a side of Leo in his private moments that show readers how he really admires people like Dave the football star and how he wants to find a way to emulate such people. He might also reveal his own kind of "not good" when he thinks about how glad he was that the research paper he did for Chad was almost ruined by the rain. We might also learn that he deliberately sabotaged portions of the paper that would bring down its grade somewhat. Again, we might see that Leo also has a kind of passive-aggressive side to his personality.

In conclusion, writers should realize the value of using private moments and character thoughts to reveal deep, yet subtle personality traits in a story's characters.